The Banyoro and their culture

The Banyoro and their culture are located in the western regions of Uganda, specifically in the districts of Hoima, Kibale, and Masindi. They speak Bantu and may be traced back to the Congo region of origin.

In the banyoro culture, people greet each other with pet names; however, when they are related, like sisters, the younger person sits on the elder person’s lap and uses their right hand’s fingers to touch the elder’s chin and forehead. This custom was shared by the Babiito clan. Following their greeting, guests were given coffee berries that were reserved for them, and they were also handed tobacco pipes to smoke.

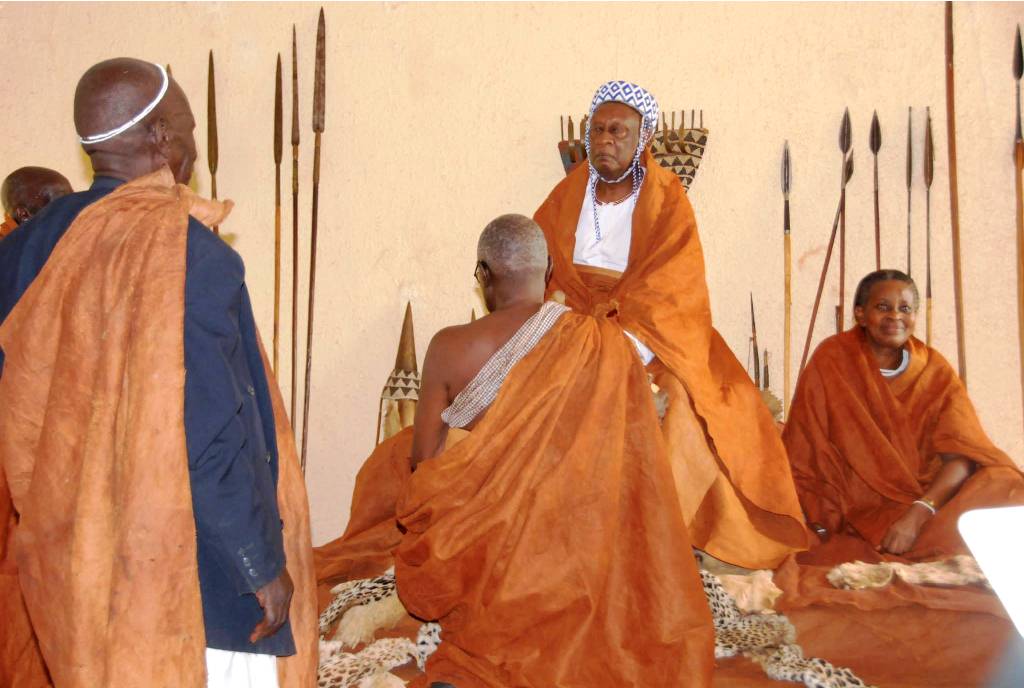

Salutations to the King

Greeting the King was never done casually; instead, they had to adhere to strict protocols. If the King was at a residence, they would publicize his presence, he would sit in the designated location for a predetermined amount of time, and subjects would come see him. This custom was called “okurata” in the local language. At different times of the day, there were several ways to address the monarch, and it was never expected of him to respond orally to greetings.

When speaking to the King, one had to use different language than when addressing ordinary males. Women had to bow down and greet him using everyday language, to which he would respond orally.

Giving birth and naming

In the banyoro culture, a girl’s name was always given after four months, and a boy’s name was given after three months. A ritual would be performed during the naming process, and the newborn would be given a name and the traditional pet name “empako.” A parent, grandmother, or other relative might name the child, but if the father was around, he always got the final say. Family names were believed to honor a relative, the circumstances of the child’s birth, or a distinctive mark on the infant.

Twins and the names that came after them had unique names, but most of them conveyed the mental condition of the person who gave them names. There were names associated with grief and death, life experiences, poverty anticipation, neighborly enmity, disaster, etc. names such as Bagamba, Bikanga, Babyenda, Nsekanabo, Alinjunaki, Balewenda, Tibanagwa, and itima, among others.

The news of giving birth to twins was cause for jubilation; the boys were named Isingoma and Kato, respectively, the elder and younger, while the girls were named Nyangoma, the elder, and Nyakato, the younger. In addition to being given unique names like Kiiza and Kahwa, the parents of the following generation were also honored and called by titles like Nyinabarongo for the mother and Isebarongo for the father. When a twin died, they never saw him as dead; instead, they flew away, a concept known as “guruka” in the same language.

Political structure

The Banyoro people lived in a centralized political system under the leadership of a hereditary ruler known as Omukama. As the most powerful individual in the kingdom, he was supported in administrative affairs by a council of notables and regional chiefs. The King commanded the armed forces as commander in chief, and each provincial chief oversaw a military unit that was authorized in their respective province.

A council of advisors known as “Bwijwara nkondo” in their native tongue—people who wore crowns made of monkey skins—helped the King. In order to demonstrate their dedication, chiefs were required to send their favored son to the King’s court and complete a political school in Mwenge.

There were other individuals who were extremely significant to the kingdom politically, such as the prime minister known as Bamuroga, the physician who was the Nyakoba from the Basuli clan, Nyamumara of the Batwaire clan, and the king who was from the Mubiito Clan. Leadership was not limited to men; the Nyakauma, the kogire rulers of Busongora, were women.

When the kingdom of Banyoro first arose, it covered an area larger than the modern districts of Masindi, Hoima, and Kibale. This was the fabled Bunyoro-Kitara Kingdom, from which the kingdom grew to become a vast empire. The Bachwezi created this empire, which eventually fell. Once the largest and most powerful kingdom, it eventually grew quite feeble and was overthrown by the neighboring territories.

In Bunyoro, the responsibilities of political power originated in the home, where the first born in the family assumed the role of the family head, known as the Nyineka in their native tongue, in the event that the head of the family passed away.

Each village had a specifically recognized elder, known as a mukuru w’omugongo, who was chosen from among the elders to serve as a go-between for them and the chiefs. The villages were politically structured. Along with a few other elders, he presided over an unofficial court that resolved disputes in the hamlet.

Relationships and marriage

In the past, finding a suitable partner was a significant matter that involved both the boy’s and the future bride’s families. The girl’s consent to the sexual relationship that followed the establishment of a domestic arrangement was a contributing factor in the entire process, which began after the girl and the boy became attracted to each other.

Wealth was not as much of a need for marriage as it was in most communities, and the Banyoro were polygamous if someone had the capacity to care for them. Due to the instability of most marriages, which made divorce common and led to a high number of informal partnerships because marriage’s survival was not legally guaranteed, bride wealth may be paid later.

Bride wealth was often paid out after a few years of marriage, or if it was determined that a certain level of stability had been reached in the marriage. Normal payment procedures would come first, but not before these arrangements. Additionally, it was common practice to look for girls in the same area, with very few people searching outside of their towns for spouses.

Empaga rituals

In order to commemorate the Omukama people’s survival to witness the new moon, the Banyoro people would assemble in the king’s courts and dance to the music performed by the men of the royal band. The men from the royal bands took part in paying for wind instruments such as flutes, drums, and relays.

In addition to an annual festival lasting nine days and a plan for a seven-day celebration held at the king’s mother’s estate, there was also a new moon ritual that may go for several days at the king’s palace. It is customary for this ceremony to take place in either December or January.

Among the pet name examples are Abwoli, Akiiki, Atwooki, and Apuuli.

Food and drink

Their main diet consists of millet, potatoes, bananas, beans, and beef; some foods are only consumed for special occasions. They would serve beef and millet to guests; potatoes were only served during periods of famine.

financial arrangement

Bunyoro was a hub of trade, and land was a valuable resource. Along with iron ore reserves close to Masindi, there was salt trafficking from the salt deposits of Lake Katwe, Kasenyi, and Kabiro. Because the Banyoro were skilled iron smiths, numerous groups traveled to Bunyoro to conduct business. The Banyoro were also skilled at producing red-hoes, which the societies to the east of Lake Kyoga much needed.

Demise

The Banyoro was afraid of dying because he believed it was brought on by ghosts, negative neighbor behavior, rumors, and well-wishers. When a person died, the elderly women in the household would shave their beard and hair, close their eyes, cut their fingernails, and wash the entire corpse. The body would then be left in the house for a while with its face uncovered, while women and children were permitted to cry, but men were not.

In the event that the family patriarch passed away, ensingonsingo—a blend of millet and simsim—was placed in the right hand. Depending on the deceased man’s wealth, each of his offspring had to wrap the corpse in a backcloth after taking a tiny bit of the mixture from his hand and eating it. Subsequently, one of the nephews was required to carry out a rite in which he had to take out the house’s central pole and toss it into the center of the courtyard. Next, remove the endiiro, or dead man’s eating basket, along with his bow. Additionally, since the fire had been extinguished for grieving, there wouldn’t be any additional fire in the house for cooking during the first three days.

A mound of the deceased man’s kitchenware was placed within the compound, along with a banana plantation bearing fruit. The deceased man’s nephew would periodically visit the well, fill a pot with water for the household, and then toss it into the mound of the deceased man’s kitchenware. In order to stop it from crowing where the main bull’s testicles were immediately constrained and to stop it from engaging in any sexual behavior during the grieving period, he also had to catch and kill a deceased man’s cock.

After four days of mourning, the ritual came to an end with the bull being killed and eaten. This practice, known as mugambuzi, involved murdering male animals. There would be no reoccupation of the deceased man’s home.

It was thought to be hazardous for the sun to shine directly on the tomb, so the burial would typically take place in the morning or the afternoon. Women were typically expected to control their crying when the body was being transported to the cemetery, and in the case of pregnant women, burial was prohibited due to the possibility of miscarriage.

Because they believed it was customary for them to assume sleeping positions and that no one had to leave the graveyard before the burial was finished, they adhered to a certain culture and buried the woman’s and man’s bodies on the left and right, respectively. The tools used to prepare the grave and the basket used to transport the dirt were left by the graveside after every burial. People would completely wash themselves and remove all soil since it was thought that if one walked in a garden wearing soil on them, all the crops would rot and wither.

In addition, after being buried, people would chop off the hair on their heads and backs and toss it on the tomb. They would then mark the grave with stones and iron rods, believing that if one erected the grave, family members would get sick and pass away.

Clay would be placed in a deceased person’s lips if they had unfinished business with someone; this was done to keep the deceased person’s ghost from tormenting the living.