Bahima and their culture

Bahima and their culture: What is the East African Hima People’s identity? In the Eastern African Great Lakes region, the Hima name is connected to a number of ethnic groups and governmental organizations. The term “Hima” refers to a subgroup of the Tutsi that arrived in the region in the 1300s, possibly as Cushite immigrants from the Ethiopian highlands.

According to some historians, the name Hima is also connected to a Nilotic people who descended from the Sudan via Uganda and the Nile. In what is now southwest Uganda and the neighboring region of Zaire, they subjugated the Bantu people. They adopted the Bantu language after becoming assimilated by the Bantu people. The main way to identify someone’s origins in a language is by their name.

In Ankole, Uganda, there is a tribe known as the Hima (Bahima). According to ethnologies, the Hima speech is categorized as a Nyankore (Nkore/Nkole) dialect. The link between individuals speaking Hima and other types of Nyankore would probably be the same as with the dialects of the Cushite Tutsis and Bantu Hutus speaking Rundi/Rwanda, according to the ethnologies, but they do add that this speech form “may be a separate language.” Tanzania does not have a listing for the Hima. The Hima seem to be confined mostly to the region where they first settled.

There has long been secrecy around Bahima’s past. John Hanning Speke, who reported in 1863 that the Wahuma (Bahima) were white people who were more civilized than black or negroes and who came to Uganda from Ethiopia, where a dominant white race was in charge, is the source of the riddle. Other Europeans said that Bahima were born to govern and had exceptional intelligence and abilities. These opinions were held by colonial missionaries, explorers, and administrators such as Samuel Baker, John Roscoe, and Harry Johnston in Uganda. They granted Bahima credit based only on physical similarities to white people, such as their long, pointed, sharp noses.

To capitalize on these characteristics and maintain their dominance over other Ugandans, the Bahima have concealed their actual background of a difficult nomadic existence and a lack of material prosperity. Let’s grasp this before attempting to debunk the myth:

The cousins Bahima, Batutsi, Bahororo, and Banyamulenge share three main traits. They (1) speak the local language and take on local names whenever they relocate, (2) oppress the native population, and (3) their men only marry members of their own ethnic group. They take the latter action to keep their secrets about controlling them a secret and to prevent others from penetrating them. However, they urge their women (apart from those in the ruling class) to wed elite members of other ethnic groups in order to win over the males to the Bahima side or gain access to their other and political secrets.

Speke reports that Bahima claimed they walked through the heart of Ethiopia or Abyssinia before crossing the Nile into Bunyoro. They changed their national identity to Wahuma, lost their religion, lost their language, and kept the unique traditional story that they were originally half black and half white in Bunyoro. Put differently, when Bahima and Speke first met, all she could recall was that they were originated from White folks.

In the second demystification, Bahima’s race is discussed. Many continue to use the physical characteristics mentioned above as proof—which is mostly subtle—to publicly but subtly argue that they are White people. In addition, they continue to maintain that they have more attractive women and are smarter than other Ugandans, with lighter complexion and thinner lips. You can easily determine who is lighter and has thinner lips by taking a random sample, which will demonstrate that they are, in fact, darker and have thicker lips than Bantu. When it comes to women, beauty is subjective, and that’s where the conversation should end.

Bahima are claiming that they are descended from white Bachwezi and not black Nilotic Luos, adding that the Basoga are Luos, in an effort to maintain their “white” background and reject their Nilotic Luo lineage. However, there’s another issue here. First of all, Bachwezi were Black people rather than White people. Bahima has had a very hard time establishing a link between them and Bachwezi thus far.

Researchers came to the conclusion that Bachwezi were a branch of the established Bantu population that started to prioritize herding. The earliest sites were inhabited by mixed farmers who had become experts at herding cattle by the time they occupied the Bigo site, according to chronological investigations of earthen works in western Uganda, indicating that these people were Bantu.

Bahima and customs

Nonetheless, Bahima have persisted in using their mystical ties to the semi-divine Bachwezi to uphold their political dominance over Bantu, particularly Bairu and Bahutu. This is not a new Hamitic myth; in fact, the idea that the pastoralist [Bahima] aristocracy had a different origin and were superior to the cultivators of the lakes region has persisted for a very long time.

Hima Ladies

It’s time for Bahima and their cousins to give up the notion that they are born rulers, light-skinned, more intellectual, and superior. It is abundantly clear from their control of Uganda since 1986 and Rwanda since 1994 that these people are not natural leaders. The superior civilization of Bahima in Uganda is the subject of the third demystification. Due to discrimination against African Americans, Europeans came to the conclusion that Bahima imported material culture and civilization from outside Uganda.

Upon meeting in the lakes region, Bantu culture was more developed than that of Bahima and Batutsi. Let’s sum up by saying that everyone wants to live in harmony, safety, prosperity, and dignity. Let us look at Article II of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which states that “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights and endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood,” as an alternative to concentrating on ethnic differences.

What we are seeing in the Great Lakes Region is opposition gaining the upper hand when these rights and freedoms are denied. It won’t go away unless we actually adopt, accept, and apply the previously cited Article II.

Tutsi and Bahima

Most people’s perception of the Tutsi is that they originated in northeastern Africa from a Cushite ancestry. Some academics have observed similarities to Nilotic. The similar circumstances of the elite classes of the Nilotic and Cushite people may have contributed to their increased association over the years. The Tutsi-Hima seem to be so tightly linked today that, notwithstanding differences in political beliefs throughout the Lakes Region, they can be regarded as a single broad class. They speak Bantu with extremely similar speech forms.

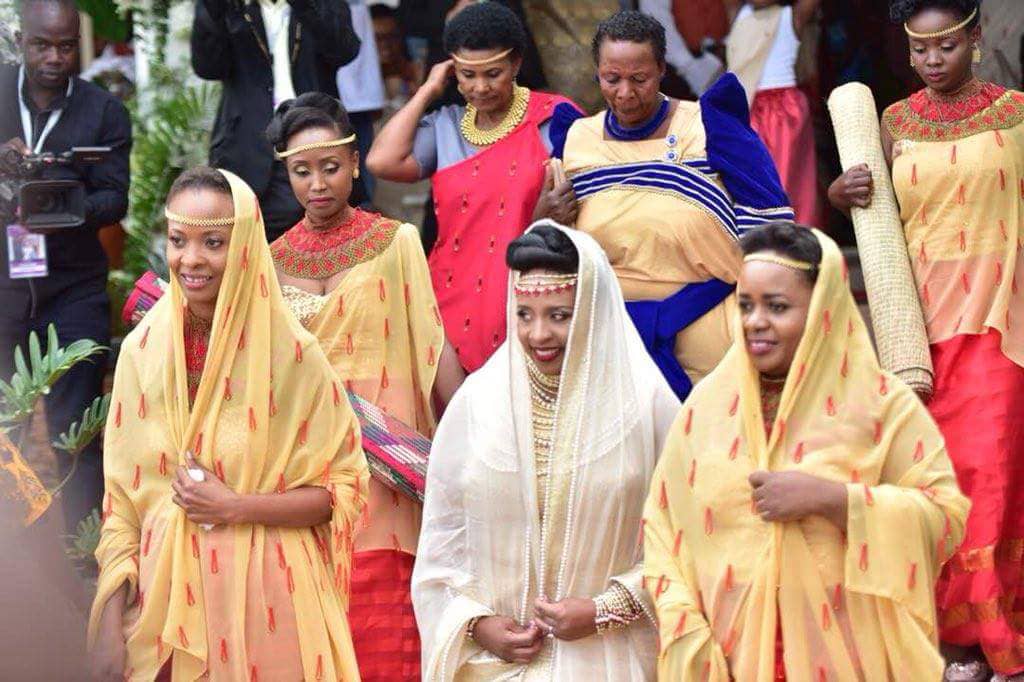

Getting ready to marry in the Bahima community

They used sticks and grass to build round houses. Even though it took a Muhima less than 30 minutes to gather all the building materials, it still required considerable expertise, and the hut might endure for many years. The Bahima spent a very long time living in communal quarters that were mostly centered around the family head’s hut. Their two large rooms are primarily utilized as a bedroom and for other purposes.

The hut’s inside was customized to fit the preferences of various households. Such was the dwelling where a Muhima bride-to-be was housed. For the future bride, an addition known as an ekitu was occasionally built. Men used a woman’s size as a proxy for her beauty. It is preferable if the woman is more obese. The notion that the bride came from a wealthy family was another justification for making her obese. It was also an indication of health.

A young woman is even now preparing for marriage in ways that will only make her appear heavier. Before now, only her immediate family members were allowed to see the bride during that fattening time.

Where the Bahima people came from

Western Ugandan cattle farmers are particularly well-known for their distinctive bond with their animals. Anthropologists categorize them as “Hamiticized Negro cattle people of North Africa origin.” Their cattle and human genomes suggest that they, along with the Batusti of Rwanda, are most likely from the Central Sahara region. Their customary unions have endured over time, in spite of the infiltration of alien cultures and religions. The elders who continue to stress the importance of cultural marriages are largely responsible for the Bahima people’s continued enjoyment of performing their traditional nuptials.

The selection of partners was influenced by preferences and prohibitions. Families took into account kinship, money, and caste when selecting a mate. For instance, it has always been forbidden for a Muhima to wed a Mwiru due to the caste system. Marriage was only accepted in society when a man and a woman were both part of the Bahima, the ruling class.

Muhima are not allowed to marry the daughters of their mother’s sisters or father’s brothers because to kingship prohibitions. Cross-cousin marriage was allowed, nevertheless. The wife’s primary responsibility was to bear children. Consequently, a man made an effort to marry into a family where women were plenty.

Finding a prospective spouse among the Bahima people

For the Bahima, choosing a prospective spouse was an intricate and fascinating process. Although it may seem unusual to say this in the modern era, neither the girl nor the guy in our society were allowed to choose their companion. It was customary for the boy’s and girl’s parents to arrange the marriage, occasionally without the parties’ knowledge.

This was a result of the ban on Bahima girls traveling alone. A Muhima girl never actually got to see you since she was always covered, and whenever she moved, her siblings were always with her. The girls would conceal themselves if you went to visit. When they were still young, the majority of individuals used to be aware that there were attractive girls in a household. And when she was six or seven years old, they would begin courting her.

The groom’s family would dispatch an emissary to convey a message to the future bride’s family once she had been identified. The messenger went by the name Kateerarume or Kyebembera.

The Bahima people deposit money for brides.

The messenger needed to be a familiar face to both families. The boy’s family would leave several cows at the girl’s house if the message was favorably received, which it usually was because parents wanted to see their daughters get married. The term “enkwatarugo” refers to these cows (the cows that keep the kraal). They demonstrated your seriousness about getting married to the girl. They represented wealth as well.

The girl’s primary purpose for the cows was to feed her until she was ready for marriage, which was often around the age of sixteen. In addition, the four cows served as security to “tie down” the young girl and deter potential suitors. According to tradition, the enkwatarugo cows would be given back to the suitor’s family after the daughter reached adulthood. That being said, the bride’s family kept the cows’ offspring.

Following that, the bride price would be negotiated between the two families. Once an agreement was reached, the bride’s family would select the agreed-upon day to pick the cattle. The best cattle from the groom’s or his family’s herd would be hand-picked by the bride’s people on that particular day. Nonetheless, some families would conceal the healthiest cows for fear of losing their best cows. In order to get the best cows, the girl’s family would occasionally send spies ahead of time.

Traditionally, if a girl’s elder sister or sisters were still single, she could not be proposed for marriage. It is stated that if a young sister received a marriage proposal, the girl’s parents, like the father-in-law of Jacob in the Bible, Laban, would control the situation and give up the elder daughter rather than the younger one.

bride price among the Ugandan Bahima in the event that the boy’s family is impoverished

A poor suitor would smear a girl with butter to claim her if he didn’t have cows for the bride payment, known as enkwatarugo. Ousigyiro was the name of this tradition. But for this act to be successfully performed, the male and the lady had to want it equally. It was meant to be the man who caught the girl and covered her whole body with butter! The woman then went to her parents and told them what had transpired.

The pre-marital sex had fostered an intimacy between the young couple that was regarded as nearly as intimate. It seemed clear that the woman, who had met the man in secret, was eager to wed him! On the overall, though, orusigyiro was not common. Once your father broke the news that your future wife had been identified, often there was excitement. Who is this woman, my future wife? What does she look like? Often times, young ladies would hide in the bush to take a sneak peek at the future wife. But woe betide you if you were caught in the act, you would be made to pay a heavy fine.

Bahima and customs

Okujugisa ceremony among the Bahima People of Uganda

This is a very important event in the marriage tradition among the Bahima. When the herdsman is to be married, his bride’s family select 10 cattle from his kraal. During the ceremony, men from both the groom and bride’s side engage in a witty debate and poem recitation in a bid to out-compete each other.

Sometimes they engaged in bitter disagreements, resulting into quarrels. But in the end, the cattle would still be selected and a date would be agreed upon when the groom’s family would deliver them to the bride’s home. After okujugisa, the fattening process begins, as the bride is prepared for okuhingira, (give-away ceremony).

Get fat quick among the Bahima People of Uganda

As soon as the cattle for bride price had been selected from the groom’s kraal, (Okujugisa) the girl was entrusted to her grandmother, to begin the fattening rituals. One of the aunts, maternal or paternal, also took on the responsibilities of fattening the girl. Sometimes they would take her with them to their homes and fatten her from there. The fattening utensils comprised a collection of well-polished and smoked ebyaanzi (milk gourds) of different shades.

She would spend months, up to six months in some instances with the fattening specialist, doing no heavy work, but eating. She would be coaxed into drinking milk in different forms like amashunu (unfermented milk) and thick fermented milk (amakamo). She was given a large gourd and tasked to gulp it all down before sun set. She was fed on ghee and roasted fatty goat meat. With such feeding, a young woman weighing 65kg at the time of identification for marriage could be as heavy as 160kg in only three months!

The girls did not like it but they had no option they had to drink it under watchful eye of an auntie who would be compelled to cane or rebuke her saying: “Why don’t you take the milk? You want to go while looking like a blade of grass? “By the time the grannies and aunties would be though with fattening her, she would be too fat to the extent that she could hardly walk. By the time she got married, the young woman would be so fat that she could only waddle.

She was not only kept in the house to be fattened, it is also widely believed that a woman who stayed indoors for long periods away from the glare of harsh sunlight became more beautiful.

On her wedding day, onlookers would comment on how beautiful she looked, noting with approval the folds in her skin caused by her obesity, and the difficulty with which she walked!

Red Ants among the Bahima People of Uganda

To instil fear in the bride and keep her inside the house during the fattening period, she was always warned of the ferocious red ants that would bite her. The bride was told that once stung by these tiny insects, she was not supposed to extract the fangs from the skin until she died!

This custom is called okumbanda empazi or okutambuuka empanzi. The intention was to make the bride committed to the marriage since she had fetched the family cows, which is considered wealth.

Okutambuuka empanzi, also helped prevent bad omen. It was regarded a taboo to wander outdoors as the girl could be raped or bitten by a snake. That’s why she would not even be allowed to go and cut wood which was usually laid on the floor or fetch water!

Here comes the bride

Typically, the average marrying age of a non-schooling Muhima girl was 16. Before the day of the wedding, she would be in a hut in the company of other girls and cry endlessly. When you passed near such a home and heard such wailing, you would know that somebody’s daughter was going to be married off. While wailing, the bride would hold onto a pillar that supported the hut as her friends smeared her with butter to make her slippery so that the bridegroom found it difficult to carry her away on the day of okuhingira. She would be beaten and rebuked by her brothers and told to stop crying.

The bridegroom would then enter the kraal of the bride’s family and be conducted to the hut the bride would be standing and waiting in. He would then take her right hand and lead her to the assembled guests. A strong rope was then produced by one of the bride’s relatives and tide to one of the bride’s legs. Sides were then chosen by the members of the bride’s and bridegroom’s clans and a tug of war would then take place. The bride’s clans would then struggle to retain their sister, and the bridegroom’s clan would strive to carry her off.

During this contest, the bride would stand weeping because she was being taken away from her old home and relatives. All this time, the bridegroom would be standing by her, still holding her and when the final pull was given in his favor, he would slip the rope off her ankle and whisk her away, a few yards to a group waiting near with a cow-hide spread on the ground.

The bride would sit on the cowhide, and the young men would raise her up and rush off with her in triumph to the bridegroom’s parent’s house chased by friends and relatives.

Bahima brides used to undergo a number of changes during and months after the marriage ceremony. Prior to the ceremony, her head and pubic hair would be shaved.

A few months after the ceremony, she would return to her village and undergo a second shaving, have her nails trimmed and her ears pierced and jewellery added.

Virginity rewarded among the Bahima People of Uganda

in the hut the bride-to-be was not only stuffed with food but she was also given advice on marriage issues. Her grandmother was one of the people who played that role of a marriage counsellor. But the main role was played by her paternal or maternal aunties, Inshwekazi. Among the Banyankole, the father’s sister was (and still is) responsible for the sexual morality of the adolescent girl. Her duty was to advise the girl on how to begin a home. More so, since in Ankole, girls were supposed to be virgins until marriage. In most instances, she did not have any experience in marriage at all.

Whenever the bride-to-be broke down and cried, given that she was going to live with total strangers, the Inshwekazi would comfort her, assuring her that all would be well. The other duty of the aunt was to prove the potency of the bridegroom by watching or listening to the sexual intercourse between the bridegroom and her niece. If a girl was found to be a virgin, she was rewarded with a young fat heifer.

If the parents of the girl were aware that their daughter was not a virgin, this information was formally communicated to the husband by giving the girl, among other gifts, a perforated coin, usually five pence of the pre-colonial East African currency or another hollow object. Likewise, if the bride was aware that she was not a virgin, she would also be given a hollow coin and politely asked to take it back home to her parents. However, the groom was never held accountable for not being chaste until marriage.

Wife by force among the Bahima People of Uganda

If a prospective bride did not like the suitor, he could resort to okuteera oruhoko, meaning he would force her to marry him hastily without her consent and much preparation. The practice of okuteera oruhoko was characteristic of the traditional Ankole society but vestiges of it still appear. Society decried this practice but it was common and often got many a young man a wife. However, the offender had to be fined a hefty bride price.

There were various ways in which this practice was carried out.

One such way was by using a cock. A boy who wished to marry a girl who had rejected him, would get hold of a cock, go to the girl’s homestead, throw the cock on the compound and ran away.

The girl had to be whisked to the boy’s home immediately because it was believed and feared that should the cock crow when the girl was still at home, refusing to follow the boy or making unnecessary preparations, she or somebody else in the family would instantly die! Another way was by smearing millet flour on the face of the girl. If the boy chanced to find the girl grinding millet, he would pick some flour from the winnowing tray used to collect the flour as it comes off the grinding stone and smear it on the girl’s face.

The boy would run away and swift arrangements would be done to send him the girl as it was feared that any delays and excuses could precipitate a calamity. Other ways of okuteera oruhuko included the suitor putting a rope around the neck of the girl and then pronouncing in public that he had done so.

Another method was to put a plant known as orwihura on the girl’s head or sprinkling milk on the girl’s face while milking. The latter was only possible if the suitor and the girl were from different clans. Oruhuko was a dangerous and degrading practice. It was usually tried by boys who had failed in the art of wooing a maiden. If such a suitor was not lucky enough to out run the relatives of the girl, he was bound to face their collective wrath.

If he escaped a thorough beating, he certainly had no way around the high bride price. He would be charged double or even more than the usual bride price rate. Moreover, the extra cattle which were charged were not refunded if the marriage collapsed.